Dramaturgy

CONTEMPORARY LITHUANIAN DRAMA: CONFLICTS IN THE PLAYWRIGHT’S ROLE

By Aušra Martišiūtė-Linartienė

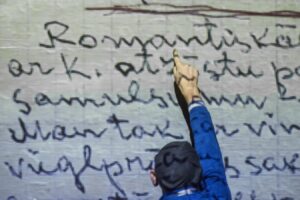

Marius Ivaškevičius, currently the best-known Lithuanian playwright in the world, was in 2018 awarded the most prestigious award, the Lithuanian National Prize for Culture and Arts, for his boldness in taking literature into the theatre. As the second decade of the 21st century comes to an end, this brave step is recognized as of remarkable value. Another exceptional theatrical success is also related to the literary value of the dramatic text – Liučė čiuožia (Liučė Skates), a play written by Laura Sintija Černiauskaitė in 2003 analysing the problems of a relationship between a man and a woman. According to Ivaškevičius, Černiauskaitė’s “works are full of captivating, subtle erotica, the style is spare, and at the same time her manner of speaking is incredibly natural, emphasized by the metaphors that turn up in the right place, at the right time”. The quality of the text has encouraged many directors to return to this play: there have been three adaptations of the play in Lithuania (from Algirdas Latėnas, who staged the brand new play, to Yana Ross and Oskaras Koršunovas), four adaptations in Russia (by V. Skvorcovas and others), two adaptations in Scandinavia and one in Italy. But the roles of a playwright are changing in the context of contemporary Lithuanian drama: more and more often, the playwright expresses himself not only as the author of an individual text, an adapter of a text selected by a director, but also as a colleague and co-author of a collective creative force – the director, scenographer, composer and actors; a combiner of documentary texts; or a performer of a text which conveys the main idea.

There should be no distinction between the literary and theatrical value of contemporary Lithuanian drama written by playwrights who have selected these roles, but changes in the playwright’s role have been influenced by many factors, including education, cultural experience and the politics of culture. The older generation of playwrights (Sigitas Parulskis, Gintaras Grajauskas, Marius Ivaškevičius, Vytautas V. Landsbergis, Laura Sintija Černiauskaitė, Herkus Kunčius and others) were born in the sunset era of the Soviet era. Its members usually have a philological education. They write not just drama but also poetry, prose and essays, and are considered to be writers in a broad sense. Some of the playwrights from this generation came from the theatre (Birutė Mar, Daiva Čepauskaitė, Nijolė Indriliūnaitė), and their dramatic texts are created on the basis of personal theatrical aspirations. The younger generation (Gabrielė Labanauskaitė, Goda Dapšytė, Indrė Bručkutė, Dovilė Zavedskaitė, Vaiva Grainytė, Birutė Kapustinskaitė, Teklė Kavtaradzė, Virginija Rimkaitė, Aleksandras Špilevojus, Justas Tertelis and others) were born in the independent Lithuania and studied the art of theatre and cinema. They were stimulated to write texts through various theatrical activities, experiments and the search for the language of theatre, as well as through words and a voice of their own.

The collisions in the playwright’s role are determined by their choice of topics, problems and material which they interpret in their dramatic works. The older generation of playwrights’ attention to the dramatic text is determined by one of the dominant topics – the modern person’s relationship with tradition, history and other texts (for instance, in his play Rusiškas romanas – Russian Romance, Ivaškevičius interprets texts by the Russian writer Leo Tolstoy and his family, while Parulskis uses the letters and autobiography of the writer Žemaitė in his play Julija). Playwrights from the younger generation focus on topics and problems related to a modern person and society. For example, personal experiences are reflected in Vienaveiksmė mono pjesė PRAdedančiam aktoriui (One-Act Monoplay for an Aspiring Actor) by Justas Tertelis and Terapijos (Therapies) by Birutė Kapustinskaitė. Other plays focus on problems which are often culturally marginalised: foreigners, consumerist society and ecology (Žalia pievelė – Green Meadow, Dreamland by Rimantas Ribačiauskas, Virimo temperatūra 5425 – Boiling Temperature 5425 by Virginija Rimkaitė, Saulė ir jūra – Sun & Sea by Vaiva Grainytė, Raudonoji knyga – The Red Book by Nijolė Indriliūnaitė).

The dotted line of tradition

The first dramas in Lithuania were written for performances of the Jesuit School Theatre in the 17th and 18th centuries. Written in Latin, the dramas reflected important cultural and educational values of the Baroque, including the aim of gaining a broad knowledge of the country’s history and accentuating relevant issues. Theatre was used to react to the important events of the state (for example, The Dialogue about Peace written by Kasper Pętkowski in 1582 revolves around Stephen Báthory’s victory in the war with the Grand Duchy of Moscow and the peace treaty with Ivan the Terrible which followed that victory). From the Jesuit School Theatre, which brought the Lithuanian Dukes to the stage, to the present day, the tradition of historical drama has been continuously developed, becoming especially active during crises of national identity. The Lithuanian Jesuit School Theatre was closely related to the development of European theatre and its artistic efforts. Most of the School Theatre’s performances were public, taking place in the courtyards, streets and squares of Vilnius and other towns where Jesuit colleges were located. Performances became a very important part of the town’s culture, consolidating society and developing its aesthetic taste. Eventually, theatre reached the nobility of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Francesca Ursula Radziwill was one of the most renowned court playwrights. Her plays were staged in the theatre of Nesvizh Castle and other Radziwiłł households. After her death, a book called Comedies and Tragedies (1754) was published.

After the January Uprising in 1863-4, the Russian Empire banned publications in the Latin alphabet as well as Lithuanian cultural activities. Lithuanian drama began to be written underground. Vincas Kudirka introduced a playwriting competition for the illegal newspaper, Varpas, in 1893. Consequently, plays written for secret Lithuanian evenings were published in Prussian Lithuania and United States: Amerika pirtyje (America in the Bathhouse) by Keturakis, historical and mythological dramas by Aleksandras Fromas Gužutis, short dramatic works, mostly comedies, by Žemaitė, Vaižgantas and other writers. In the countries which were not affected by the ban on publications, dramas were written for amateurs and performed by Lithuanian communities (the Tilsit Lithuanian Singers’ Community, which performed dramas, comedies and mystery plays by Vydūnas, was a rare phenomenon). Playwrights were well aware of their main tasks: bringing the community together, strengthening the public spirit, as well as encouraging Lithuanian national identity and dignity, and preparing society for the life of a free, independent Lithuania.

When Independence was restored in 1918, professional theatre was established. Petras Vaičiūnas, who had an excellent knowledge of society and theatre, became the most popular playwright. He wrote dramatic texts to fulfil the ideas of the directors Borisas Dauguvietis and Andrius Oleka-Žilinskas. It was Vaičiūnas who wrote the adaptation of Šarūnas, a play by Vincas Krėvė. Directed by Oleka-Žilinskas in 1929, this play is defined as an epoch-making event. At the same time, a team of mature writers turned to playwriting. Most of them expressed themselves as literary researchers, drama and theatre critics but didn’t have a direct connection with the stage: the prose writer Vincas Krėvė, the poet and prose writer Vincas Mykolaitis-Putinas, the poet, theatre critic and ideologist Balys Sruoga, the patriarch poet Maironis, the modernist poet Kazys Binkis and others. The dramatic works of these writers are among the most valued classics of Lithuanian literature: Valdovo sūnus (The Master’s Son, 1921) by Vincas Mykolaitis-Putinas, Skirgaila (1924) by Vincas Krėvė (1924), and Milžino paunksmė (The Giant’s Shade, 1932) by Balys Sruoga.

The tradition of Lithuanian playwriting is dominated by historical drama. During the Soviet period, dramas revolving around Lithuanian historical figures and events became a significant form of cultural resistance: Herkus Mantas (1957) and Barbora Radvilaitė (1972) by Juozas Grušas, Mindaugas (1968), Mažvydas (1977) and Katedra (Cathedral, 1971) by Justinas Marcinkevičius, and Grasos namai (House of Menace, 1971) by Juozas Glinskis. Playwrights raised historical awareness and brought the community together. After the restoration of Independence in 1990, historical drama changed slightly – verse dramas were replaced by prose texts, while playwrights resolved to bring silenced episodes, personalities and events back to historical memory. They focused on the early 20th century and topics which had been forbidden during the Soviet period. Interesting personalities who had contributed to Lithuanian culture during the interwar period were rediscovered. Painful historical lessons were accentuated: the loss of independence, Soviet occupation, and exile to Siberia (Mergaitė, kurios bijojo Dievas – A Girl Whom God Was Afraid of by Gintaras Grajauskas, Malыš (Sweet Kid) and Madagaskaras (Madagascar) by Marius Ivaškevičius, Bunkeris (The Bunker) and Visiškas Rudnosiukas (The Complete Brownnoser) by Vytautas V. Landsbergis, Ledo vaikai (Children of Ice) by Birutė Mar and others. It can be stated that playwrights have created a continuous account of Lithuanian history, starting from the establishment of the Lithuanian state (Šarūnas by Vincas Krėvė) through to the liberation from the Soviet empire in the late 20th century and the experience of the independent country. They reveal this account through the theatrical language of their own generation (P.S. Byla O.K. – P.S. Case O.K. by Sigitas Parulskis, Barikados – Barricades by Goda Dapšytė and Jānis Balodis, and Pašaliniams draudžiama – Keep Out by Gintaras Grajauskas).

Speaking with the voice of one’s generation

The language and form of a dramatic work assert not only the search for individuality but also the generation of the authors and ways of expressing co-cultural communication. Modernist trends and avant-garde experiments have brought together groups of authors who shared the repertoire of topics and means of expression (for example, in his play Generalinė repeticija – Dress Rehearsal (1939-1940), Kazys Binkis focuses on the problems of connecting illusion and reality, art and life and the way of expressing these problems as suggested in Luigi Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author, 1921).

There were only a few attempts during Soviet times to speak the generational language which was created by the Theatre of the Absurd and other avant-garde movements in Lithuania, because avant-garde experiments were generally not tolerated by the censors. Kazys Saja’s grotesque Mamutų medžioklė (The Mammoth Hunt, 1967) as well as the Absurdist plays Duobė (The Pit), Maratonas (Marathon) and Pirmadienio popietė (Monday Afternoon) written for student theatre by Arvydas Ambrasas and Remigijus Midvikis in 1967-1970 are among the exceptions. The most remarkable representative of Lithuanian avant-garde playwriting of the late 20th century is Kostas Ostrauskas. Like other expatriate playwrights such as Algirdas Landsbergis and Antanas Škėma, he moved to the United States after World War II. Ostrauskas stayed abreast of the creators of Absurdist drama (his first play, Pypkė – The Pipe was written in 1951). Gradually, he began writing postmodern intertextual dramas (Ars amoris, 1991), experimented with theatre, music and art (Kvartetas – Quartet (1969), Belladonna (1992-93) and others) and established a characteristic genre of microdrama (usually, the text of a microdrama is comprised of a few lines, but the microdrama Paskutinis monologas – The Last Monologue contains only one word, written in cursive script as a remark: “Silence”). However, the majority of Ostrauskas’s plays didn’t reach the stage. On the other hand, Kęstutis Nakas’s tetralogy When Lithuania Ruled the World (1986-2004), written in the United States, was primarily meant to be performed. The dramatic text was created with the cultural context and the audience’s expectations in mind. These expectations were shaped by the Off-Off-Broadway movement in New York, avant-garde plays and performances. Viewed in the wider cultural context, Nakas’s tragifarce is an avant-garde work, closely related to the tradition of Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi (1896).

P.S. Case O.K. (premiered in 1997, directed by Oskaras Koršunovas), which has been recognized as the most remarkable avant-garde work in Independent Lithuania, illustrates the changed role of a playwright. The stage adaptation of this play is regarded as a significant event which changed the poetics of drama and theatre. According to Audronis Liuga, “the director, along with the playwright Parulskis, the composer Gintaras Sodeika and the artist Žilvinas Kempinas didn’t merely “deconstruct” the traditional canons of drama, heroism and scenic beauty. Parulskis adapted the story of Abraham and Isaac, the myth of Oedipus and the tragedy of Hamlet for the modern young person’s existence; the director turned the “incidents” of Soviet school and army into archetypal rituals of initiation, patricide and matricide; the artist placed the action into an “apocalyptic” installation with a target gleaming at its centre in the depths of the stage, while meditative, contemplative music “drowned” the audience into the bottom of a certain “pit of memory”. Parulskis’s play emphasizes the newly independent society’s maximalist moral obligation to build its new life on an uncompromising loyalty to the truth. Instead of interpreting an already written dramatic text, the playwright was involved in the process of the play’s adaptation, writing the text as it was being staged. The accents of the play’s meaning emerged from the collaboration of the playwright, director, scenographer, composer and actors.

The playwrights of the younger generation also often express the voice of their generation using a reliable cultural basis: that of antiquity – in the text Hotel Universalis, Indrė Bručkutė transfers the Phaethon myth to the contemporary world; that of old myths of various cultures, which are important to Aleksandras Špilevojus, the author of 12 gramų į šiaurę (12 Grams Northward); that of the Bible – in Gabrielė Labanauskaitė’s play Raudoni batraiščiai (Red Shoelaces), the destinies of the brothers can be associated with the story of Cain and Abel, while in Teklė Kavtaradzė’s Keletas pokalbių apie (Kristų) (A Few Conversations About (Christ), the Christianity is not accentuated and is only expressed implicitly as the characters discuss the problem of faith and faithlessness; and that of analysing the phenomenon of democracy (Mindaugas Nastaravičius’s grotesque Demokratija – Democracy). The search for dramatic form is influenced by the direction (especially when the text is written by the director himself, such as Špilevojus), but the dramatic text can stand on its own as a fulfilled creative work.

Analysing society through playwriting: towards a creative collaboration

The identity problem of a contemporary person is revealed in plays focusing on topics such as emigration, ethnic minorities and the lives of other marginalized people. The playwright chooses the role of researcher or sociologist, attempting to disclose certain problems of the community (Išvarymas – Expulsion by Marius Ivaškevičius, Žalia pievelė – Green Meadow, Dreamland by Rimantas Ribačiauskas, Red Shoelaces by Gabrielė Labanauskaitė, Barricades by Jānis Balodis and Goda Dapšytė, Lė-kiau-lė-kiau (Let-Pig-Let-Pig) by Daiva Čepauskaitė, and others.

Focusing on the topic of emigration, Ivaškevičius’s play Expulsion became one of the most popular shows in Lithuanian theatre (directed by Oskaras Koršunovas at the Lithuanian National Drama Theatre). Unlike exile, emigration is a voluntary choice, but the social and economic reasons that determine this choice reveal its dramatic intensity. Ivaškevičius spent half a year in London while writing Expulsion, researching the life of the emigrants whose stories came to be the basis of the play.

The name of the play, Išvarymas (Expulsion), has a double meaning. The slang word išvarom translates into “we’re leaving, going away, clearing off”. This play is, therefore, about the people who have willingly left, or “cleared off” – young, strong, confident, adventurous. On the other hand, the name has an opposite meaning that signifies coercion: this is a play about people who have been expelled. The meaning of this word conceals the underlying social and philosophical meanings of the play itself. The protagonist, Ben, as well as other characters of the play are expelled from home – from Lithuania. As the emigrants try to make their way through illegal means, they are also expelled from English society.

The analysis of personal experience is one of the key features of contemporary Lithuanian playwriting (Dovilė Zavedskaitė’s play Dramblys – The Elephant reconstructs a mother’s biography; Birutės Kapsutinskiatė’s play Therapies (staged at the Oskaras Koršunovas Theatre in 2017 and directed by Kirilas Glušajevas) was created from real situations recorded in a diary. These situations were experienced while nursing a mother who had oncological disease and observing other women around her.) In her play, Kapustinskaitė talks about women suffering from oncological diseases and their private life in the corridors of a hospital where not everyone is allowed entry. But when one is allowed in, it brings tears, as well as tears of joy. Kapustinskaitė has a degree in screenwriting. Characteristically, her text has the quality of a good documentary – the ability to depict reality. Critics emphasize the textual value of the play. According to Ieva Tumanovičiūtė, the dialogues feature “recognizable situations and characters who are not banal but tragicomic, where their representative character acquires a shade of comedy or tragedy, while the general blends into the original”.

Plays based on personal experience denote a change in the playwright’s role too. Produced by the Atviras ratas laboratory theatre in 2004, Atviras ratas (Open Circle), a show of autobiographical improvisations (directed by Aidas Giniotis), doesn’t have a playwright at all – the text is composed from the actors’ stories and confessions. Barricades (2014), created at the National Drama Theatre, has been defined as a journey of young artists into their childhood and into the most tragic night in Lithuania’s history – 13 January 1991. The Latvian director Valteris Silis, who co-created Barricades with Lithuanian actors, is a supporter of creative collaboration. The development of the show therefore began without a dramaturgic basis – that is, without a play. The dramaturgy was combined from historical facts, actors’ improvisations and fantasies by two playwrights – Latvian-born Jānis Balodis and Lithuanian-born Goda Dapšytė. The text was produced by selecting the most interesting ideas which emerged during rehearsals and by the search for an answer to the question which the team of artists deemed the most important: what does freedom mean to the first-ever generation that doesn’t have to fight for it?

The dramaturgy of Apie baimes (About Fears, 2017), a family play of installations staged at the State Youth Theatre, is constructed by an even larger team: playwright Teklė Kavtaradzė, director Olga Lapina and artist Renata Valčik. Kavtaradzė “collected“ the dramaturgy for this play from the stories, notes and belongings of the actors. Nevertheless, the essence of the play is authentic feelings which turn into a universal, relatable experience through the area of installations built by the scenographer.

The upsurge in documentary drama is demonstrated by an interesting example of creative collaboration – the show Green Meadow (2017). The creators of the show were nominated for the Golden Cross of the Stage Award for best dramaturgy, proving the significance of co-creation in contemporary Lithuanian drama. The text of Green Meadow is composed of stories told by former and present workers of the Ignalina Nuclear Power Plant. However, the essence of this kind of work is the idea which encompasses both the topic and the choice of theatrical realization. The show’s concept and text are created by directors Jonas Tertelis and Kristina Werner as well as Rimantas Ribačiauskas and Kristina Savickienė from the Lithuanian National Drama Theatre. The team of creative collaboration is joined by the characters – who are not actors, but the actual residents of Visaginas who go on to tell their own personal stories and express their opinions on stage. Nežinoma žemė. Šalčia (Unknown Land. Šalčia) about the people of Šalčininkai region is another documentary theatre performance. Its dramaturgy is constructed by Andrius Jevsejevas and Eglė Vitkutė, while the text was also produced from material of the artists’ research. The dual quality of the characters was possibly introduced as a reaction to the criticism of Green Meadow: the characters are both actors who engage in the research and interviews and the people from Šalčininkai who tell their own stories. The documentary theatre therefore begins to experiment with new topics and forms of drama, drawing the attention of the artists and the audience to the contemporary life of the Lithuanian countryside and marginalized communities. But it is through these small communities that the life of contemporary Lithuania, also a small community in the context of Europe or the world, can be sensitively revealed and appreciated.

Another change in the playwright’s role is to be found in the experimental theatres established by young artists: the performances of the theatre movement No Theatre, founded by director Vidas Bareikis in 2011, are based both on contemporary plays and collective texts written by the creative team when implementing an idea. In the performance Telefonų knyga (Telephone Book, 2011), its director Bareikis and the playwright Marius Macevičius are co-authors of the play/script. Meanwhile, there is no playwright in the performance No Awards (2013) – actors speak the text which they have written themselves. The performances of the Apeiron Theatre, founded in 2012 by the young directors Greta Gudelytė and Eglė Kazickaitė, are also based on creative collaboration; the presentations of the shows indicate “authors and performers” but the position of a playwright is not mentioned at all in the programmes of most of the performances.

Initiatives to change the playwright’s role

Change in the playwright’s role has been determined not only by subjective choices and artists’ ideas, but also by initiatives of the theatrical world. The strategies of the Versmė National Drama Festival, organised by the Lithuanian National Drama Theatre, influence the nuances of new plays and their adaptations which are included in the repertoire. The Festival has been taking place since 2005 with the aim of providing opportunities for new plays to emerge on theatre stages in Lithuania. In the last few years, this has been supplemented by new educational aims. Playwrights are provided with knowledge of the processes of contemporary theatre and gain experience of creating new forms of theatre. In 2017, the Festival’s main theme was documentary theatre. Not only playwrights but everyone contributing to contemporary theatre was encouraged to focus on principles of creative collaboration and to team up. Creative seminars were led by experts/practitioners of documentary theatre from Germany, Great Britain and Poland. In 2018, artists were invited and encouraged to focus on creative stage works which, according to Martynas Budraitis, “synthesize social and political realities. We imagine that this is a performance whose creators inquired and listened, and now they retell what they have heard, conveying relevant and authentic stories through various means of theatre and interdisciplinary arts”. In 2019, the organisers of Versmė chose a theme defined as “Small stories, big histories”, inviting artists to look for relevant topics and interesting stories in (auto)biographies. The theme of the 2020 competition is utopias/dystopias. Thus, the landscape of contemporary Lithuanian playwriting and theatre, especially the production of texts for this kind of theatre, is being shaped by direct institutional endeavour. Attention to specific topics and new forms of drama and theatre which reveal them is encouraged.

Concluding remarks about the playwright’s role in contemporary Lithuanian theatre could include a statement that the choice of collective creativity, which has emerged in addition to individual creativity, is liberating; it also allows new, talented young people to be drawn into the orbit of theatre and its life. The playwright has the opportunity to become a co-author of collective creativity, getting to know the theatre process from the inside, and expressing important ideas through interdisciplinary artistic means. However, these kinds of texts involve a risk of being “one-offs” or of eliminating a playwright from the theatrical process. The literary value of a text written individually by the playwright provides an opportunity for the theatre creators to produce a performance with deeper meanings; the manuscript can turn into a book, which, just like the performance, is an integral part of the meaning and prestige associated with a playwright’s creative work. An individual creative piece might cross the existing boundaries of the performative factor of drama, going on to become a post-theatrical drama, or a fine dramatic text – and, as Heiner Müller stated, the dramatic text can only be considered fine when it can’t be staged by any existing theatre.