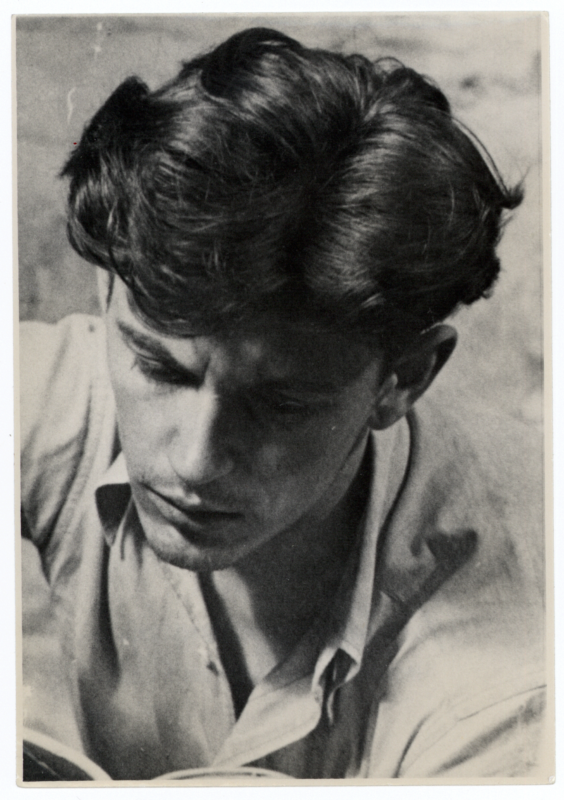

Kostas Ostrauskas

Photo from Institute of Lithuanian Literature and Folklore archive

The playwright, literary historian and critic Kostas Ostrauskas (1926-2012) established a genre of playful and intellectual drama. After World War II, he moved to Germany and later to the United States. Ostrauskas’s early works (written during the ’50s and ’60s) experiment with the poetics of the Theatre of the Absurd (Pypkė – The Pipe, 1951, Once There Lived an Old Man and an Old Woman, 1963–1997). During the ’70s and ’80s, Ostrauskas’s works started featuring the ideas of postmodernism, while his dramas were rich with allusion to the classics of Lithuanian and world literature. The trademark genres of Ostraukas’s dramatic works are micro and mini dramas. He produces the artistic reality of his dramas from a rich cultural reservoir – literature, music, art. His cycle of four dramas, Metai (Seasons, 1968), is based on Antonio Vivaldi’s violin concerti Four Seasons. Ostrauskas’s play Kvartetas (Quartet, 1969) offers a particularly musical language and remarkable musical form. His play Gundymai (Temptations, 1983), based on the paintings by Hieronymus Bosch, is an interpretation of the fine arts. Literary classics play an especially important role in Ostrauskas’s playwriting. He playfully connects Maironis’s lyrical ballads Jūratė ir Kastytis (Jūratė and Kastytis) and Čičinskas with William Shakespeare’s tragedy Hamlet (Duobkasiai – The Gravediggers, Hamletas ir kiti – Hamlet and Others, Shakespereana), as well as works by Samuel Beckett, the classic of the Theatre of the Absurd.

The Theatre of the Absurd dominates in Ostrauskas’s creative work. It becomes especially visible in Who is Godot? (1999). Ostrauskas interprets Beckett’s most mysterious drama, Waiting for Godot (1952), searching for an answer to the questions which keep intriguing readers and critics to this day: who is Godot? What lies behind the limits of the space which holds the characters captive? What keeps the characters from opening the “closed door” and looking at the reality beyond the walls? The Theatre of the Absurd offers people an opportunity to return to themselves, which, according to Ostrauskas, is its greatest value. Each of the anonymous characters in Who is Godot? must, before finding the answer to this question, first discover the answer to “Who am I?”