Kęstutis Kasparavičius: a conductor of the world’s imagination

(An article was published in “7 meno dienos”, 2016-05-27)

From April 6-29, during the Bologna Children’s Book Fair, the city’s Art and History Library (Biblioteca d‘Arte e di Storia di San Giorgio in Poggiale) hosted artist Kęstutis Kasparavičius’ retrospective exhibition “Conductor with a Paintbrush.” The Exhibition presented 30 years of his creative work through more than 100 illustrations and books. The exhibition was organised by the Lithuanian Culture Institute together with Julija Reklaitė, the Lithuanian cultural attaché in Italy.

Bologna is a special place for the illustrator’s biography: this is where he received the honourable UNICEF “Illustrator of the Year” award (1994) and the “Award for Excellence” (2003), and it’s where his illustrations were selected for the exhibitions of an annual illustration contest 13 times. Displays installed in Bologna’s library allowed the exhibition’s visitors to inspect every detail of Kęstutis Kasparavičius’ works up close, travel the labyrinths of his work and imagination, open every door, gaze out every window…

According to exhibition curator Dr. Jolita Liškevičienė, this is exactly what is essential about this exceptional Lithuanian illustrator’s work: it is encoded with a force that frees the imagination. We spoke to J. Liškevičienė and K. Kasparavičius about their experiences in Bologna and about Kęstutis Kasparavičius’ creative path, which was illustrated by the exhibition. We met by the artist’s table, where the entire “chorus” of characters he had created was born (as well as the idea for this exhibition).

How did you formulate the exhibition’s concept?

Jolita Liškevičienė: Here’s how it actually went: each of us had our own vision, and Kęstutis did not originally agree with mine.

Kęstutis Kasparavičius: Jolita wanted the exhibition to include all of my work from the very beginning – from the “Crafty Art Lessons” I published in 1984. It didn’t seem worthwhile to me – after all, I had started as a chorus conductor at the M. K. Čiurlionis School of Art and only completed my design studies at the Vilnius Academy of Arts at age 26. Until then, I had never even tried illustration. It just so happened that soon after, in 1990, I began working with German publishers. I think that the beginning of my work was was what other people do while they’re still students. I learned by drawing my first illustrations!

JL: I, however, think that it’s worth showing this stage as well. The “Lithuanian Fairy Tales” published in 1989 was a large-scale significant work, as well as “The Adventures of Baron Munchhausen” (1987). After all, an artist cannot reach maturity immediately and it’s interesting to observe their development. Kęstutis’ first book illustrations are different from the ones we know now and he used different techniques – he coloured with watercolours and he used hatching to create depth. At the time, Kęstutis Kasparavičius was learning a lot about art history and looking for prototypes. We also saw the first signs of surrealism. We presented all of this in the first part of the exhibition as his search for his own style. Beginning in 1992, his style began to change significantly. There was a break that coincided with the influence of the German context. Over a decade (until 2002), Kęstutis Kasparavičius became what he is today, perfecting the aesthetics of nonsense and other unique aspects of his work.

How much was that influenced by German publishers’ commissions?

KK: In 1990 I earned the “Golden Pencil” award in Belgrade, which opened the path to international orders. My work with the publisher of the German city of Esslingen was definitely not easy and my experiences with Vaga and Vyturys had been completely different – I did whatever worked and nobody ever had any comments. Here, everything was different: I sent sketches to their art editor, Matthias Berg, redrew my work several times and perfected it. There were many requirements, and they could even ask me to change my techniques – and I did. At first, I ground my teeth and thought that my hatching really hadn’t been that bad… but I am now glad that I passed muster. I think that the first couple of books weren’t that great, but I did gather momentum after that.

JL: The German publishers had rules, strict illustration counts, and demanded that their deadlines be met.

KK: And I couldn’t argue because they were high-level experienced professionals who had told me, by the way, that they prefer working with young artists. I think that this experience is what made me a real illustrator.

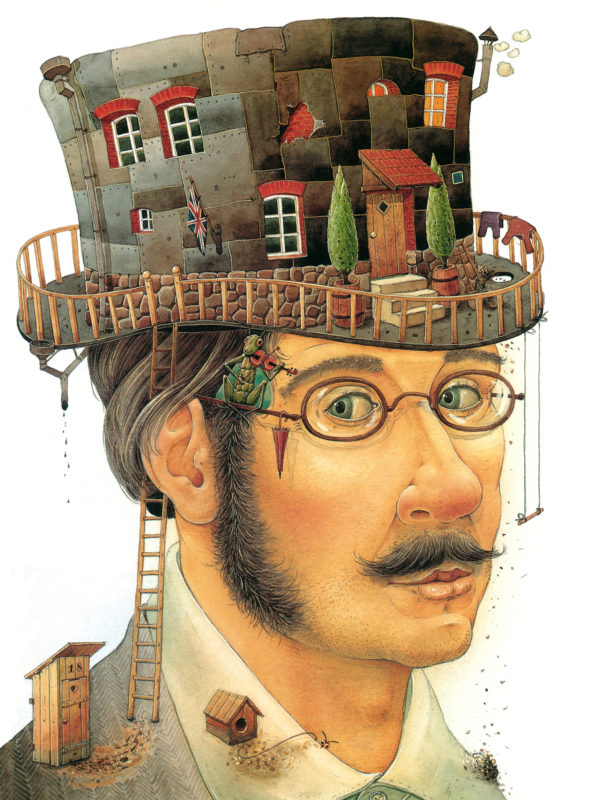

JL: At this stage, what liberated Kęstutis Kasparavičius’ imagination the most was his illustrations for Edward Lear’s book “The Duck and the Kangaroo” (Esslinger, 1992). Lear is known as the forefather of nonsense aesthetics in children’s literature. I believe that this commission was fateful for Kęstutis: he finally had the opportunity to work independently of the text. We used an illustration from this Lear book on the cover of the Bologna exhibition’s catalogue because it captured the essence of Kasparavičius’ work: it was a portrait of the book’s author and a self-portrait of the artist all in one. The hat is like the imagination, which has various doors, steps and windows inviting the reader in. The period between 1992 and 2002, which we referred to as the main stylistic formation period in our exhibition, also liberated the artist’s characters, and his illustrations began to include stories. At this year’s Bologna children’s book fair, I participated in a discussion where the participants asked – how can we tell whether an illustration is good for a book? That’s when you become a participant in the illustration and you feel as if you’ve entered it when you look at it.

By the way, we also identified two other stylistic directions during this period in Kęstutis Kasparavičius’ work. As he strengthened his nonsense aesthetics, he also illustrated classical works: “Pinocchio” (Coppenrath Verlag, 1993) and “The Nutcracker” by the same publisher (1998), “Thumbelina” (Nieko Rimto, 2005) and other books. As we know, all books include realistic and fantastic spaces, and it is the latter, without a doubt, that Kęstutis is closer to. The third direction was realistic aesthetics. Kasparavičius created illustrations for Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s “An Honest Thief” (Grimm Press, 1994). He also began working with Americans – the Boyds Kills Press publisher needed only realism.

KK: That was my darkest period… I certainly didn’t want for work: I continued working with the German publisher and also received commissions from Taiwan. But I wanted to test myself in the English-speaking world. It turns out that was a mistake… It was uninteresting, boring, and there were no special editions or sales. I made a few books: “Saint Valentine,” “Saint Martin,” more saints’ biographies, and h. Ch. Andersen’s “The Little Match Girl.” However, I started writing after that!

The Taiwanese publisher Grimm Press initially want to write a story for one illustration, publishing a book with several authors for charity. The first story was called “The Twittering Person.” When this book was published, the publisher’s chief asked me: your story was rather fun – are there more? I didn’t have anything else, of course, but I lied and said I did! I had no idea how many they would need. It turns out they needed 36. Basically, we agreed on a month (that was supposed to be so I could get them in English). I wrote all of the stories in two weeks. The first book – “Short Stories,” I believe – is fairly erratic. But it seemed like everyone liked it, so I continued by writing a second, a third, and others… Then, the publisher Nieko Rimto appeared in Lithuania and began to publish my books in Lithuanian.

JL: In 2003, Kęstutis Kasparavičius became a writer and an artist. This stage has continued until now!

How do you enjoy writing?

KK: When you start writing at 48, you can’t even imagine how many ideas you have in your head until you start writing and they come flooding out – I barely had the time to write them down! The first books tumbled out one after the other. Later, I probably began using my words better, editing them and slowing down. I think my later texts are better.

Could your texts exist independently or, say, with the work of another illustrator?

KK: I don’t think so… After all, my stories are like expanded explanations under the illustrations. Usually, I think of an image first that then dictates the text. It would be strange to see that someone sees my story differently… but perhaps it would be OK?

JL: What is truly characteristic of Kęstutis Kasparavičius’ illustrations is that they awaken the imagination. Some of his illustration books have had several different texts made for them! Let’s take “Tinginių Šalis” – this book was initially published in German (with the artist’s own illustrations), then in Mexico, where a Mexican writer wrote a new text. Then there were Danish, Korean and Greek version, and one in Lithuanian created by Vytautas V. Landsbergis.

JL: It would truly be an interesting study to compare all of the texts and see what we could learn from different understandings of the images, different interesting cultural nuances.

What was your relationship with classical story texts like?

KK: When I created illustrations for stories or other authors’ texts, I’d “clean out” my ego, read the text many times over and try to understand it.

Would you take on such work now?

KK: No, I would no longer want to – it’s not interesting. The last story I illustrated, “Thumbelina,” was a decade ago…

What do you think about current publishing fads, trends and directions?

KK: European publishing features very strict classification according to children’s age groups. Picture books are now more framed, the relationship and format between the illustrations and the text are all set, and so on. My books, like “Short Stories,” for example, are completely “off topic,” but such books are almost never published any more. It has to be a 32-page book, one story, with a text from 800 to 1,000 words. Now, I’ve become interested in trying out these limits, and I’m creating three books in a row according to this standard. It’s hard to shorten your text so that the idea and the humour would remain, so it wouldn’t just be a brief explanation of the illustration.

JL: Now you create about one book a year, correct?

KK: Yes, I’m not in a hurry! For about ten years, I’ve been working for my own pleasure, and nobody has hurried me anywhere or pressured me.

What do you think made you a universal international phenomenon? Your books’ journeys through different countries began right when you began working. Why?

KK: Well, yes, things went well for me – as soon as I sent my sketches to, let’s say, the Bologna children’s book festival, they were selected…

JL: Kęstutis Kasparavičius is simply unique and different, whether in Lithuania or anywhere else in the world. He’s an artist who found his creative direction, which is seemingly simple but can’t be compared to anything else. I think you’d have a hard time finding artists creating anything in the “Kasparavičius style.”

KK: Maybe because other styles are not only beautiful, but they sell as well. My books have never been best-sellers! Publishers choose me, but it’s not like they’re pouncing on me jealously… Even Matthias Berg once wrote to me: In Germany, you have a certain group of “fans” who like you very much and buy everything, but this group is not very large. An edition of a certain size is bought out and that’s it. However, that group is stable. I think that might be a good thing. Perhaps nothing good would come of it if I intentionally tried to create something more popular.

How does your location affect your work?

KK: My location and environment are very important. I draw a lot of nature. When I lived on the city outskirts in a house, my illustrations had a lot of nature, which I was surrounded by at the time. Later, I moved to Vilnius in the Old Town, and my books began to feature motifs from my evening walks. If I were to wind up in New Zealand, I’m sure I’d begin drawing differently.

JL: Kasparavičius’ illustrations don’t just have a lot of environment, they have autobiographical details – he often includes himself as well! If you’d walk through his home, you’d recognise several vases, interior details, pieces of furniture or bannisters.

KK: I’ve drawn my own children many times until they grew up and refused to pose. I had dressed my son in a borrowed monk’s habit and he posed as one of the saints. It was funny when he stepped out with the whole habit onto the balcony to smoke. I wonder what the neighbours thought.

Let’s return to Bologna: the opening of the exhibition drew many fans of your work and publishing professionals.

JL: There was truly a large audience. Book art specialists know Kęstutis Kasparavičius’ work and value it. It would be great to organise this exhibition in Lithuania as well!