100 Years in One Month: The Discovery of the Baltic World out of the Spirit of Music

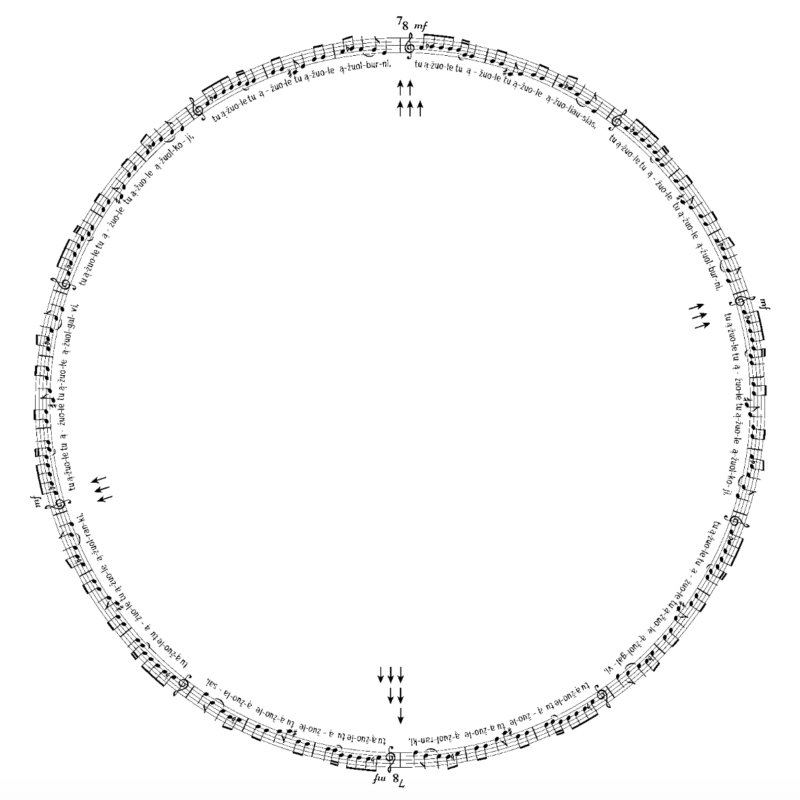

A Fragment of Bronius Kutavičius’s score for the oratorio Last Pagan Rites, 1978. Music Information Centre Lithuania, 2018.

The territorial expansion of the Baltic tribes in pre-Christian Europe and its acute decline in the modern Western era is a riddle that has inspired several generations of scholars and artists. The poetics of historical memory and forgetfulness were strikingly revealed in the work of Bronius Kutavičius as a radical turning point in Lithuanian music and a manifesto of cultural freedom in the Soviet period. It provided the impetus for the composer’s cycle of four ethnooratorios – one of the most significant artistic reconstructions of the Baltic world in terms of its impact. In this way from the 1970s on the composer created a vision of musical renewal out of the discovery of the Baltic world.

With this cycle Kutavicius joined the circle of global artistic expressions and academic concepts, stirring up change in the understanding of historicity and otherness in the times of a post-modern turning point – from the authentic performances of the ‘world music’ movement, the ‘New Middle Ages’ of Arvo Pärt, Tolkien’s fiction and magical realism to the research into Baltic culture by Marija Gimbutas, Algirdas Greimas and Norbertas Vėlius or the currents of the ‘new historicism’.

Kutavičius’s four oratorios merged into the story of the historical fate of the Balts and revealed the composer’s concept of historiosophy. The story should begin with the efforts of the Yotvingians to express the world: the world view of the nation that became extinct in the 13th century is expressed by the sound of stones taken from the fields of rhythm, archaic instruments and ultimately by several random phrases, written down in the historical chronicles of their conquerors and neighbouring nations. The Dzūkai (the Lithuanians living in southeast Lithuania), who live in a part of the lands formerly inhabited by the Yotvingians, sing of their own world using several melodic motifs – primordial intonations extending bodily gestures, intonations flowing forth in an archaic Dzūkian folk song (the oratory From Yotvingian Stone, 1983). The comparison of two worlds is Kutavičius’s formula of musical historiosophy, use in his oratorios as well. The uncontrollable or wild Baltic cult energy (Panteistinė oratorija / Pantheistic Oratorio, 1970) seems to be balanced by the harmony of the symbolic archaic order of the world (Pasaulio medis / Tree of the World, 1986), while the organ – the symbol of Christian culture – overshadows the pagan rites of worshipping nature (Paskutinės pagonių apeigos / Last Pagan Rites, 1978).

The composer does not take it on himself to decide which world was more perfect, to judge or justify. He has discovered a pagan Baltic soundscape buried in the deep past, with the help of his intuition and imagination. And beyond the historization of poetics there lies hidden a more fundamental and more important question to a contemporary composer – how to find one’s own style and an original way to give voice to the world in musical sounds if one does not want to blindly obey the forced manner of modernisation, which the centres of culture insistently press on one? Relying more on the artist’s intuition, opening up to ancient memory, Kutavičius’s ethnooratorios can be derived from a vision of the archaic proto-language of humankind, language-music or proto-music – one of the various impetuses which provoked the return of musical modernity to its origins.

Rūta Stanevičiūtė